Avoiding Stock Market Losses Yields Huge Returns

One of the most important investment issues facing an equity (stock market) investor, if not THE most important, is the avoidance of investment losses. Oddly, this is rarely discussed by investment advisers despite the fact that, in our opinion, it is far more important than virtually any other variable affecting long term investment returns. Topics discussed include an explanation of how losses cripple returns, common strategies used by investment managers to counteract this problem and why they are ineffectual, and lastly, a description of how Summit Investment Management deals with this issue.

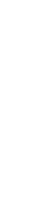

Any discussion of this topic must begin with an understanding of the variability of stock market returns. We will use price only returns to the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) to illustrate our points.

In the one hundred thirteen (113) years since the turn of the 20th century, the DJIA has produced positive annual price returns (excluding dividends) seventy-three (73) times. In other words, there have been forty (40) years of negative calendar returns.

This means that the DJIA has declined approximately thirty-five percent (35%) of the time on an annual basis.

An investor, therefore, should expect that on average, over a 3 year holding period, there is likely to be one year with a negative return. While that is a statistical fact, it doesn’t always play out that way in reality as the DJIA has had winning streaks of 4 or 5 consecutive years and even one (in the 1990’s) that lasted 9 years as well as losing streaks of 3 or 4 straight years in duration.

“So what?” the investor might well ask. The DJIA produced a return of 19,731% over that time period or 4.79% annually. An initial investment of $1,000 would have become $197,307. Isn’t that good enough?

To answer that question, let’s see what happens to results when we manage to avoid those 40 years of negative returns. We will assume that when the historical market return is less than zero (0%), instead of a negative return our DJIA portfolio return is now zero (0%). No losses are allowed. Obviously, the returns will be higher, but how much higher?

It turns out that by staying even when the market declines makes a world of difference in performance. The results, in fact, are so good that they are difficult to comprehend.

Instead of a compound return of 19,731%, this “no down year” DJIA garnered a total return of 24,151,084%.

That equates to an average annual return of 11.59% or 6.80% more annually, on average, than the DJIA actually returned with both up and down years. That initial $1,000 investment would have grown to $241,510,837.

Over a century is a very, very long time for an individual. It can be within the investment horizon of a wealthy, multi-generational family, a corporation, foundation, or trust, however.

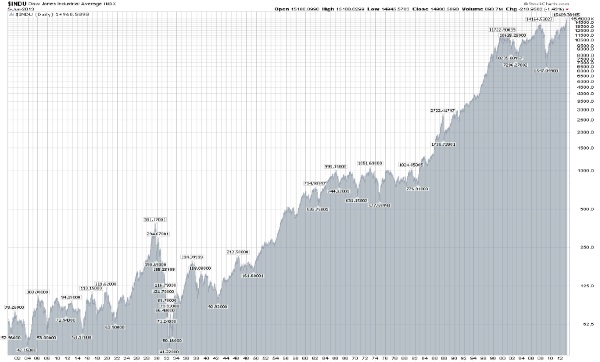

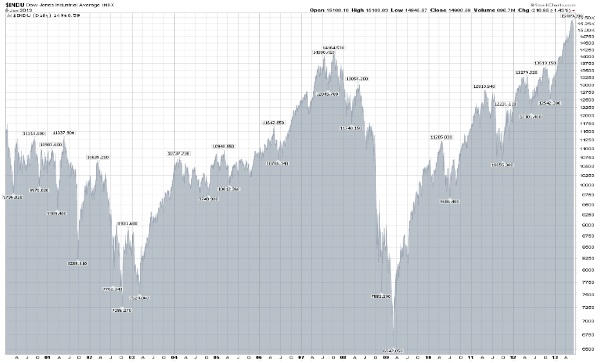

But to bring this concept into focus for most investors, let’s look at the experience since the turn of the 21st, rather than 20th, century. In the thirteen (13) full years that have passed since New Year’s Eve 1999, the DJIA has had eight (8) years of positive returns (2003, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012) and five (5) years of negative returns (2000, 2001, 2002, 2005, 2008).

This is slightly more negative than our full period would have led us to expect, with about a thirty-eight percent (38%) occurrence of negative results (35% over the 113 year period). The DJIA produced a total return of just 13.98% in that time, or a paltry 1.01% per year on average. Without any loss years, those figures become 138.89% and 6.93%, respectively.

Let’s take this one step further. Rather than limit our study to calendar years, we will now eliminate any market declines of 10% or more, whenever they may happen during our study period. Our analysis shows that since 1900, the DJIA has tumbled ten percent (10%) or more on seventy-seven (77) different occasions. That equates, on average, to once every 536 days or approximately once every eighteen months.

The worst uninterrupted decline of –64.71% came, not in 1929, but between November, 1931 and July, 1932. The market plunge in 2008 – 2009 was the second worst on record, dropping 49.86% from top to bottom.

Starting with our latest 2000 – 2012 period and eliminating those falls of ten percent (10%) or more has an even greater effect than our calendar year experiment showed. Over the course of those years, there have been eleven (11) periods in which the DJIA dropped more than ten percent (10%). By eliminating these losses, the total return for the thirteen year span increases to 1,597.66% or 24.34% per annum. An initial investment of $1,000, therefore, would have become $15,976.61 rather than the $1,139.80 that was possible through the loss including DJIA.

For the full one hundred thirteen (113) year period, the elimination of any market declines of ten percent (10%) or more results in a truly “jaw-dropping” return. If you wish to learn more about the full period effect, please contact Summit. It is clear that, solely from a return perspective, there is a strong case for the importance of avoiding losses.

But there is another perspective that is also quite compelling in its own right.

To understand this additional perspective, consider the following scenario. One million dollars ($1 million) has been amassed to fund a future project. That project can be of any nature whatever; retirement funding, or philanthropic giving for example.

When a severe market downturn hits, long held plans can be jeopardized. Often the sponsor/investor is left with one of two poor choices. To preserve the principal of the fund, disbursement amounts can be cut. This can ensure the survival of the project longer term but may cause severe disruptions near term as funding is reduced.

Sometimes, as is the case with mortgage obligations, disbursements cannot be minimized. In such cases, the principal amount can be irreparably damaged as the periodic fixed payments represent a much larger percentage of the remaining principal. Principal can be prematurely exhausted, leading to an untimely project end. In either case, the project being funded will suffer. The only real difference is in the timing.

Common Investment Management Responses

Investment managers, recognizing, at least to some extent, the problem posed by losses, commonly resort to the use of three common “remedies”. The first remedy, and the oldest, is diversification. Market timing, or the moving of funds from one asset class to another in the hopes of avoiding a decline is the second. The third remedy is to restrict equity investments to “value” stocks.

If we look at the major asset classes of Treasury bills, bonds, and common stocks we are struck by a dilemma. The most attractive asset on a return basis, common stocks, is the least attractive on the basis of return variability. Conversely, Treasury bills are the most attractive asset in terms of return variability but least so when it comes to returns.

The typical manager response to this conundrum is to recommend a diversified portfolio.

The investor thereby gains some return stability at the cost of lower returns. Ah, but the manager will say, because these asset classes sometimes move independently of one another, the risk-return tradeoff is superior as measured by something called the Sharpe ratio!

Unfortunately, you can’t spend your Sharpe ratio. Lower returns are lower returns and that means that, at the end of the day, you will end up with less money in your account than you would have had you owned only equities, unless, of course, your accumulation period happens to end coincidentally with a stock market decline.

Investment managers who market time are working to keep their clients’ funds invested in the most attractive asset at any given moment. There are many variations of this strategy from managers who will completely exit an asset class to those who will slightly tilt their asset weights in response to whatever types of signals they may use.

Those signals can be based on economic changes, interest rates, price movements, seasonality or any of a host of possible indicators or combinations of indicators. What they all have in common is that they tend to miss crucial turning points in market direction. Therefore, assets are often unexposed or under-exposed to some of the biggest return days.

In the stock market it has been estimated that missing just the best 25 days of returns to the S&P 500, for example, would reduce the return of an investor from 9.8% to just 6.1% (for the period 1970 through 2011). That’s twenty-five (25) days out of a total of ten thousand six hundred thirty-seven days (10,637), or just .24% of the days over the period of the study. That is an incredibly small margin for error. To miss less than one fourth of one percent of the possible investment days and wind up with an annual return that is reduced by thirty-eight percent (38%) is shocking.

Timing the market, therefore, is highly risky as it could lead to the missing of those crucial return days.

Value investing has a long and successful history. It has shown itself generally superior to a growth based approach to the stock market in periods of market decline. But it is not a panacea as the most recent severe stock sell-off illustrates.

The Summit Approach to Loss Avoidance

We have now seen the nature of the problem and the most common steps taken to deal with it. Returns can be greatly enhanced if losses are avoided. Diversification, while it can reduce losses, can also result in reduced returns. Market timing is highly risky. A value based portfolio doesn’t always provide its owner with protection from a generalized market decline.

Through its expertise in options, Summit has developed an approach that addresses the issue of avoiding losses without diluting returns through diversification, taking on the risk of market timing, or blindly trusting in the shield of value investing.

What Summit has done is to develop a technique whereby it hedges an equity portfolio by building various option positions around it. The portfolio hedging strategy employs exchange listed options that increase in value as the market retreats, thus reducing losses incurred by the underlying portfolio.

The portfolio is hedged in a manner calculated to build a cash reserve as the options approach expiration.

This cash reserve is then reinvested in the under-lying equity portfolio. As the market moves up or down, the option positions are adjusted to compensate. All hedges, reinvestments, and adjustments are governed by a set of rules so that the risk of poor decision making in times of stress is eliminated. Funds are fully invested (except for any minimal cash reserve) at all times, thus removing the risk of missing crucial market return days.

Avoiding Losses Turns the Stock Market into a Wealth Creating Machine

The stock market is an excellent vehicle for the creation of wealth. Unfortunately, it is also a vehicle that is subject to frequent “crashes” which act to retard or undo the wealth creation process.

We have seen just how powerful an engine of wealth it could be if only losses could be avoided.

Standard investment management efforts to avoid losses come with their own problems of diminished return and risk. Summit has developed an approach which, while it does not eliminate losses, shows great promise in its ability to significantly reduce the adverse effects of market declines.